The Magnificent Yankee

Louis Calhern’s remarkable career as a Broadway and film actor from the 1920s through the 1950s (he died in 1956 at the age of 61) included memorable performances in such diverse classics as Duck Soup, Notorious and The Asphalt Jungle, as well as the title character in Julius Caesar (1953). Yet his greatest acting showcase may have been his performance as U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes (1841–1935) in The Magnificent Yankee, a role he created on the stage and reprised for the 1950 film version.

The credited source material for The Magnificent Yankee is the 1942 book Mr. Justice Holmes by Francis Biddle, who had been one of Holmes’s law clerks and went on to serve as attorney general under Franklin Roosevelt during most of World War II. In 1943, Voldemar Vetluguin (later the producer of the films East Side, West Side and A Life of Her Own) wrote a script treatment for M-G-M, based on the Biddle book, but playwright Emmet Lavery ultimately played the pivotal role in bringing Holmes’s life to the stage and screen. While researching Holmes’s life, Lavery consulted with Biddle as well as with John Gorham Palfrey, the executor of Holmes’s estate, Tom Corcoran, another of Holmes’s former law clerks, and Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter. Lavery asked Frankfurter if he felt there would be any “impropriety” in his writing a play about Holmes and Frankfurter replied, “No, the only impropriety would be if it were not a good play. I go on the theory that Holmes belongs to the country, and anyone who wants to know about him should be encouraged.” Lavery’s play covered: Holmes’s 30-year career as a Supreme Court Justice (1902–1932); his relationship with his wife, Fanny Dixwell Holmes (her maiden name was mysteriously changed to “Bowditch” for the film version); and the parade of law clerks who Holmes viewed as the sons he never had (Frankfurter saw this as a bit of dramatic license on Lavery’s part).

The play opened on New Year’s Eve 1945 in Washington D.C., with Calhern as Holmes and Dorothy Gish as Fanny; Biddle was unable to attend, as he was in Germany presiding over the Nuremburg war crimes trials. The play moved to the Royale Theater on Broadway, opening on January 22, 1946, and running for 159 performances, but despite the show’s relatively brief run, United Artists producer Benedict Bogeaus (The Bridge of San Luis Rey, The Diary of a Chambermaid) purchased the screen rights with the intention of casting a younger actor as Holmes, possibly Gregory Peck. That same year, Lavery managed to use his appearance at the House Un-American Activities Committee hearing to promote Yankee: refusing to name names, he told the committee that a better way to advance the cause of anti-Communism would be to “dramatize the American way of life,” feeling it would be better to demonstrate “how good Mr. Holmes was than how bad Mr. Stalin is.”

Shepard Traube acquired the film rights to Yankee in 1949 and announced plans to produce and direct an independent film version, with Lavery adapting his play and Calhern reprising his stage role. Ultimately, the film would go into production at M-G-M in the summer of 1950, with John Sturges directing the Armand Deutsch production and Lavery writing the script. The 89-minute screen version understandably shortened Lavery’s three-act play but added scenes in the Supreme Court’s chambers as well as location footage of Washington D.C. Lavery consulted with the young actors playing Holmes’s “sons,” while a piece in Time magazine listed several of Holmes’s traits left out of the movie version—such as his “regular excursions to Washington’s burlesque houses, his well-thumbed library of spicy stories, his ear-curling, off-the-bench vocabulary”—and noted that Holmes’s personal secretary in 1929, the accused spy Alger Hiss, unsurprisingly went unmentioned in the film.

The film version of The Magnificent Yankee begins in 1902, when Holmes and his wife Fanny (Ann Harding) move to Washington D.C. as he begins his tenure as a Justice of the Supreme Court. A visit from Congressman Adams (Ian Wolfe), grandson of President John Adams, reminds Fanny of the loss they feel over being unable to have children, but soon Holmes views his parade of law clerks, a new one every year, as the sons he never had. During his 30 years on the Supreme Court, Holmes sees his close friend Louis Brandeis (Eduard Franz) join him on the bench, and while disappointed that he will never be named Chief Justice, he becomes one of the most respected Justices in the Court’s history. Fanny falls ill and dies, but not before making him promise to stay on the Court as long as he feels able. He keeps his word, not retiring until he nears his 91st birthday, and as the film ends he is back at home, preparing for a visit from the new President, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Calhern discussed his work on Yankee (and his plans to star in a Broadway revival of King Lear) in an August 1950 Los Angeles Times profile, claiming that he was featured even more in the film than in the stage version, where Holmes was offstage for a total of three minutes: “I advised Metro executives and our director, John Sturges, on the Magnificent Yankee set about my qualms. I said, ‘Now you have even eliminated my three minutes offstage in this version. How on earth are people going to stand seeing big-nosed Calhern throughout this entire picture?’ ‘Ah,’ they said, ‘but we can cut away from you; center on some other character; do just what you were able to accomplish on the stage; manage it technically.’ So you may hear the voice of Calhern booming in the background, but you’ll be watching the reactions of beautiful Ann Harding. That is definitely where pictures have an edge on the theater and can make things easier on the actor.” A month later, the Times announced that actor Philip Ober, who played Holmes’s friend Owen Wister (best known as the author of The Virginian) was being brought back to add narration to the film, but the narration in Yankee serves such an important function in tying incidents spread out over 30 years into a 90-minute narrative that it is strange to think this could have been an afterthought.

The film premiered on December 20, 1950, just in time for Academy consideration, and reviews were mixed to favorable, with Newsweek terming Calhern’s work “a robust, theatrically effective characterization of the great man,” and Cue praising it as “a splendid portrait.” Even Merle Miller in the Saturday Review of Literature, who called the film “The Magnificent Disappointment” and accused the filmmakers of making “one of this country’s intellectual and spiritual giants into a dull-witted midget,” saw Calhern’s work as “something of a miracle.” The New Yorker was particularly harsh in its view of the film’s abridgment of Holmes’s lengthy career, remarking that “the film plainly has little time for Holmes’s forensic activities, most of it being devoted to the Great Dissenter’s whimsicalities, such as chasing fire engines, trespassing on lawns to pick flowers for his wife, and figuring out his theory of clear and present danger in relation to free speech by chatting with Justice Brandeis and a parrot at the Washington Zoo.” Their reviewer was even critical of Calhern, who ”seems dead set on making Justice Holmes a lovable old codger, so full of chuckles and mischief and general euphoria that it is hard to believe he ever worried about any legal problems more serious than those usually handled by desk sergeants.”

These criticisms are not unwarranted, for it is a little frustrating that—73 years after Holmes’s death—the only film to feature him as a major character gives such short shrift to his great work on the bench. If nothing else, however, the film proves an excellent showcase for Calhern, who showed admirable restraint in adapting his stage performance for the screen and made one truly believe in the greatness of Holmes. Yankee was the second of four films John Sturges directed for Deutsch in fairly rapid succession, coming right between Right Cross and Kind Lady, and while the opening scenes demonstrate some impressive camera movements, the rest of the film betrays its stage origins fairly clearly: the entire play is set in Holmes’s library, and the majority of the film retains that setting. Calhern earned a Best Actor nomination for his performance, his only Oscar nod, with the award ultimately going to José Ferrer in Cyrano de Bergerac (Walter Plunkett’s costumes were also nominated).

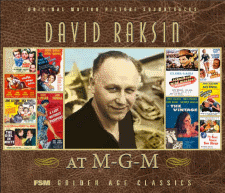

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences began announcing pre-nomination short lists in the technical categories in 1950, and David Raksin’s music for Yankee made the 10-film short list but ultimately failed to earn a nomination. (Variety called Raksin’s score “effective without intruding.”) Raksin scored all four of the Sturges-Deutsch collaborations of the early 1950s, and just as Calhern’s performance dominates The Magnificent Yankee, Raksin’s theme for Holmes dominates his score. This Americana-tinged melody first appears in the lively main title, and Raksin varies it impressively throughout the score, the versatile theme proving both thoughtful and festive depending on the needs of the scene.

As Holmes’s relationship with his wife is one of the story’s principal threads, Raksin develops the Holmes theme into a charming waltz for Fanny, which features an interpolation of the standard “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square” (a surprising choice, since the song was not published until 1940, five years after Holmes’s death).

Befitting the importance of history in the film, both Holmes’s memories of the Civil War and his groundbreaking judicial decisions, Raksin incorporates some classic tunes into his score: “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” for a scene in which Holmes visits the Civil War battlefield where he fought four decades earlier (track 15); and “Auld Lang Syne” for the film’s sentimental centerpiece, where Holmes is visited on his 80th birthday by all his “sons” (track 19). For the introductory shots of Washington D.C., Raksin uses a third principal theme, a somber melody suggesting the gravity of Holmes’s responsibilities on the Supreme Court; the score concludes with a stirring reprise of this theme over the final cast credits. —

David Raksin’s score for The Magnificent Yankee is mastered from ¼″ monaural tapes of what were originally 35mm optical masters, with a few cues (otherwise lost) filled in from acetates.

- 13. Main Title

- Raksin’s noble main theme for Oliver Wendell Holmes receives a triumphant orchestral reading during the opening titles. A contrastingly subdued but still dignified theme for Holmes’s Supreme Court responsibilities appears on solo horn for a shot of the Washington Monument, the melody gathering strength over further imagery of the capital’s landmarks as narrator Owen Wister (Philip Ober) announces the story’s key players. A chipper rendition of Holmes’s theme concludes the cue as he disembarks from a carriage outside a potential new home for himself and his wife, Fanny (Ann Harding).

- 14. Welcome to Washington

- Raksin introduces Fanny’s tender triple-meter theme when she shows up late to Wendell’s tour of the house. The melody conveys the couple’s love and respect for each other, even as Holmes pretends to be irritated upon learning that Fanny has already ordered all of their furniture shipped to this address. Raksin mixes a quotation of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” with the main theme when Holmes recalls his days as a Union soldier during the Civil War; the cue closes with Fanny’s material as Wendell agrees to buy the house and the couple leaves to visit the site of one of the battles in which Holmes fought.

- 15. Spottsylvania

- A frolicking suggestion of Fanny’s theme plays as she and Holmes arrive at the site of Bloody Angle, a pivotal battle that changed the course of the Civil War. The main theme appears briefly before “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” unfolds reverently for Holmes describing the battle to Fanny. The Supreme Court theme is dialed out of the film when Fanny reassures a doubtful Wendell that he will “have a chance at greatness in Washington.”

- 16. To The Supreme Court

- An unscored sequence in which Fanny expresses regret over not being able to have children results in Holmes’s decision to treat his secretaries—a new one each year—as his sons. A brief imitative setting of the main theme follows as Wendell and Fanny travel to the Supreme Court, where Holmes will be sworn in as a Justice.

- First Secretary Sequence

- Wister’s narration describes the first two years of Holmes’s life as a Justice, with the main theme underscoring a montage of his secretaries at work. The melody continues for Holmes enjoying springtime in Washington and climbing over a park fence to pick a crocus for Fanny.

- Second Secretary Sequence

- Wendell is chastened after Theodore Roosevelt publicly insults him for opposing the Sherman Anti-Trust Act; Raksin gives Fanny’s theme a bustling treatment as she and Wendell cheer themselves up by running down the street to watch firemen at work. Reflective developments of the Supreme Court theme underscore a subsequent montage of Holmes training his law clerks over the years, the cue resolving as Wendell’s friend Louis Brandeis (Eduard Franz) pays him a visit.

- 17. Third Secretary Sequence

- Raksin reprises the main theme once more for a montage of several years elapsing as Holmes educates more secretaries.

- Waltz From Griebene Girl

- A source waltz rendition of Fanny’s theme for strings and harp sounds as Wendell and Fanny dine at a fancy restaurant. Congressman Adams (Ian Wolfe) joins them at their table and expresses his disapproval that Woodrow Wilson wishes to name Louis Brandeis the first Jew to the Supreme Court. Wendell and Fanny are delighted for their friend but acknowledge that his appointment will not come easily.

- The Fight for Brandeis

- A solemn development of the main theme plays for Brandeis addressing the press while a Senate committee debates his nomination to the Supreme Court. The cue ends as the film transitions to Wister making his first onscreen appearance, visiting his old college friend (Holmes) at home.

- 18. Holmes and Brandeis

- The Holmeses are thrilled when Brandeis finally receives his confirmation to the Supreme Court after six months. The Supreme Court theme plays for a montage of Wendell and Louis serving together, intercut with footage of Holmes’s clerks leaving to fight in World War I. Warm, contrapuntal readings of the main theme sound as Holmes and Brandeis take walks through Washington to discuss issues of child labor and freedom of speech during times of war.

- Crocus

- After spending 19 years earning his reputation as “The Great Dissenter” in Washington, Holmes has retained his appreciation for the simpler things in life; the main theme plays as he once again visits the park and plucks a crocus.

- 19. Auld Lang Syne

- On Holmes’s 80th birthday, Fanny surprises her husband by gathering all of his former secretaries at the house. An impassioned string arrangement of “Auld Lang Syne” plays as they form a line to congratulate their mentor, who acknowledges each of them as “son.”

- 20. Fourth Secretary Sequence

- At Holmes’s birthday celebration, his former secretaries, all Harvard grads, sing “Gaudeamus Igitur” (familiar from its use by Johannes Brahms in his Academic Festival Overture). The score adopts the tune for a final montage of Holmes’s next batch of secretaries at work over the years, before the main theme sounds as Wendell passes through his favorite park. He shows signs of age as he reaches through the bars of a fence to pick a crocus, rather than simply climbing the fence as he used to.

- 21. Farewell

- Before Fanny dies of old age, she makes Holmes promise that he will not retire on account of her death but remain on the Supreme Court until he is content to leave. A lengthy cue consisting of aching developments of Fanny’s theme and the main theme is mostly dialed out of the film for Holmes’s bittersweet final moments with his wife on her deathbed. The last 0:50 of the cue fades in with a haunting Lydian variation on Fanny’s theme on solo violin as Wendell reads to her.

- I Am Content

- The Lydian variation of Fanny’s theme gets a soaring treatment when Wendell visits his wife’s grave. A pure rendition of her theme plays on clarinet, strings and harp for a shot of her tombstone.

- 22. The Day Comes

- While the Supreme Court is in session, 90-year-old Holmes briefly falls asleep; forlorn strings imply Fanny’s theme as he awakens and realizes that it is time for him to retire. Once the session ends, the main theme tentatively grows out of Fanny’s material as Holmes bids Brandeis farewell and tells him he will not be back.

- An impish rendition of Fanny’s theme sounds for Holmes watching children play by the Reflecting Pool near the Washington Monument. He asks to see one of the boys’ paper planes—made out of a newspaper—and reads a headline announcing his retirement.

- Holmes Retires

- A tender version of Fanny’s theme sounds as Holmes takes in the reality of his retirement by the Reflecting Pool; “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” plays in counterpoint to a reverential setting of the main theme for his subsequent visit to the Lincoln Memorial.

- 23. End and Cast Titles

- Holmes’s former secretaries take turns looking after him in his old age. After the former justice reveals that he will be leaving the majority of his estate to the United States government, his housekeeper announces a surprise visit from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who seeks advice about the country’s economic crisis. As Holmes stands at attention in his library awaiting his new commander-in-chief—prepared to tell him to “fight like hell” for his country—the main theme is once again joined by “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” the cue building to a triumphant conclusion for the end title card. The “Cast Titles” are scored with a rousing processional version of the Supreme Court theme.

- 24. Main Title (alternate version)

- This earlier, lighter arrangement of the “Main Title” is missing the dramatic upper-register string writing from the version used in the film. —