Quo Vadis

Music and Effects ReconstructionThe Bible has been a favorite source for filmmakers ever since the days of D. W. Griffith (Judith of Bethulia, Intolerance). Strong narratives with deep communal appeal offer one obvious explanation for this affinity—and the material was freely available in the public domain. The opportunity to recreate a past age amid lavish visual pageantry was a natural for the cinema. So, it must be admitted, was the opportunity to present (with guaranteed church approval) stories tinged with sex and violence. The biblical spectacular flourished during the silent era, but faltered with the coming of sound and was nearly extinct by the time of World War II. Cecil B. DeMille, the Hollywood director most closely associated with the genre, had not made a biblical film since 1932.

Hollywood revived the genre after the war, when large budgets became possible and the trials of the war years heightened religious sentiment among movie patrons. That Hollywood was falling under suspicion of Communist sympathies made a return to pious subject matter even more appealing. Color and (later) widescreen and stereophonic sound also promised to be formidable weapons in the looming competition with the new medium of television. The success (at least in Europe) of the Franco-Italian Fabiola (1949) may have paved the way. DeMille returned to the genre with Samson and Delilah (1949) and 20th Century-Fox announced its David and Bathsheba for 1951. M-G-M, the wealthiest of Hollywood’s studios, did not stint in this field. Metro’s epic would be a new version of Quo Vadis, filmed in Italy as the most spectacular production of them all.

The source was the Polish novel Quo Vadis? (1895) by Henryk Sienkiewicz, a book that enjoyed international renown—Sienkiewicz later received the Nobel Prize—and that, together with the American Ben-Hur (1880) and the English Last Days of Pompeii (1834) and Fabiola (1854), helped spark an international vogue for the quasi-biblical tale. Sienkiewicz’s story had been filmed at least three times previously, most notably in a spectacular 1913 Italian production, a full-length feature that preceded The Birth of a Nation by a full two years. It had also inspired a derivative English stage version by Wilson Barrett called The Sign of the Cross (1896), which eventually became the source for DeMille’s 1932 film of the same title.

M-G-M’s planning for a new Quo Vadis stretched back to the mid-1930s, when Robert Taylor was a rising young star. There had even been a scheme to make the film in Mexico during World War II, but the project as we know it took shape after the war. John Huston, known for tough dramas like The Maltese Falcon and Treasure of the Sierra Madre and for his realistic war documentaries, was Metro’s curious choice to direct. Huston envisioned a dark story that would emphasize the Holocaust parallel in Nero’s persecution of the early Christians. With Gregory Peck and Elizabeth Taylor cast in leading roles, Huston and producer Arthur Hornblow Jr. actually went to Italy in 1949 and proceeded to spend a great deal of M-G-M’s money on preparations. But studio chief Louis B. Mayer hated Huston’s approach. The director often recounted the bizarre episode when Mayer summoned Huston to his home one Sunday morning, sang Yiddish songs for him, and (according to Huston) actually fell on his knees to kiss the director’s hands and beg him to make a more sentimental and family-friendly movie. In the end, there was Communist labor trouble in Italy, Gregory Peck fell ill, shooting was postponed for a year, and Huston and Hornblow managed to extract themselves from the project to make a film more to their own taste: The Asphalt Jungle. Studio veterans Sam Zimbalist and Mervyn LeRoy were engaged to produce and direct a colorful entertainment more in the traditional M-G-M mode.

Zimbalist, a veteran producer with modest credits in Tarzan movies and other standard fare, had managed the complex African production of King Solomon’s Mines (1950). LeRoy had made crime pictures for Warner Bros. (Little Caesar, I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang) and such M-G-M successes as Random Harvest, Thirty Seconds over Tokyo and Little Women. Three writers received credit for the script that had taken shape in the early 1940s: S. N. Behrman, Sonya Levien and John Lee Mahin. The best known of these was Behrman, a playwright (No Time for Comedy), journalist and longtime M-G-M screenwriter (Queen Christina, A Tale of Two Cities, The Pirate).

Set during the reign of Nero (A.D. 54–68), the Sienkiewicz original focused on a cynical imperial courtier, Petronius, and his military friend, Marcus Vinicius, whose love for the imperial hostage Lygia (a ward of the state) brings him into contact with the feared and misunderstood underground sect called Christians—and into possible competition with the dangerous emperor and his lustful empress, Poppaea. Failing to win Lygia’s love through abduction and violence, Marcus eventually comes to admire the courage of the Christian community. But after Rome burns in a spectacular Neronian immolation, the emperor scapegoats the Christians and condemns them to the savage Roman custom of facing beasts in the arena. The finale, curiously for a story purporting to hymn the courage of the martyrs, has a nonviolent slave, Ursus, killing the bull that threatens Lygia, while hero and heroine escape to live happily in Sicily. It is the world-weary Petronius who dies in an act of belated protest—Nero’s last victim before the mob rises in revolution against the vainglorious tyrant.

There is no true biblical content in the tale, but the apostles Peter and Paul are introduced to link the church of Rome and its Lord. The famous title (usually rendered as “Whither goest thou, [Lord]?”) comes from the Gospel of John (Chapter 13, recounting the Last Supper), where Peter asks Jesus where he is going and Jesus answers, “Where I am going, you cannot follow me now, but you shall follow me afterward.” There the remark presages both Peter’s nocturnal denial and his eventual martyrdom decades later. Sienkiewicz puts the question into Peter’s mouth in an entirely different episode: Fleeing Rome on the Appian Way, Peter experiences a mystical encounter with Christ. In this legendary scene (derived from the second-century Acts of Peter), the Lord answers that he is going to Rome to be crucified a second time, Peter remembers his earlier failure and turns back to face his own martyrdom.

The screen story shifts the emphasis heavily toward the young lovers, ultimately portrayed by a mature Robert Taylor and Hollywood newcomer Deborah Kerr. The Christian background, including some old-fashioned Bible-postcard-style flashbacks, is provided by Finlay Currie and Abraham Sofaer as the apostles Peter and Paul. Subtler characterization and genuine wit mark the other Roman roles, played by the silken-voiced Leo Genn as the cynical courtier Petronius and the multitalented Hollywood newcomer Peter Ustinov as Nero.

Yet casting and story are almost beside the point. What M-G-M’s Quo Vadis really aspires to is spectacle. “This Is the Big One!” proclaimed the lurid posters, “the most genuinely colossal film you are likely to see for the rest of your lives.” On this level, the film certainly delivers. It was the most expensive film ever made to that point, a historical recreation on a vastly larger scale than Paramount’s Samson and Delilah or Fox’s David and Bathsheba. Indeed, settings and crowd scenes—a military triumph, the arena, the burning of Rome—dwarf anything in the much-ballyhooed Fox production of The Robe (1953), although the latter more often finds its place in the history books, thanks to its introduction of widescreen exhibition.

Metro’s achievement was made possible by a superior art department. Edward Carfagno and William Horning, working under the direction of the legendary Cedric Gibbons and with the support of special effects under A. Arnold Gillespie and extraordinary matte paintings by Peter Ellenshaw, created not only a spectacular city for the crowd scenes but—what is more important—a convincing one. Villas, streetscapes and the Christians’ nocturnal gathering places all looked remarkably lived-in. Cheap Italian labor was the other key factor: While the publicity department trumpeted bulletins about filming the story in the very places where the original events took place, the studio’s real motive was financial. The lavish construction and the hordes of extras available at Rome’s Cinecittà would have been out of the question in heavily unionized Hollywood. Quo Vadis, as much as any single film, inaugurated the era of “runaway production” that would become such a sore spot for the industry in the studio system’s final decade. In this respect, as in so many others, the film transcends its dramatic shortcomings to stand as a milestone in the history of epic cinema.

Critical reaction was unenthusiastic. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times admired the spectacle but dismissed the story as “downright childish and dull,” an example of “the most hackneyed Hollywood style.” Even Christopher Palmer, annotating a 1978 record release, had to admit that the film “was not good enough to be taken seriously.” Nominated for eight Academy Awards, Quo Vadis did not receive a single Oscar. Nevertheless, the film’s huge financial success opened the gates for dozens of similar biblical-historical “epics” from Hollywood and beyond. Louis B. Mayer (by now departed from M-G-M) had been right after all. Audiences were indeed hungry for history and religion on the big screen. One year after the release of Quo Vadis, M-G-M announced plans for its remake of Ben-Hur. In that film the epic genre would at last find a measure of dignity. But it was the 1951 Quo Vadis that had pointed the way. —

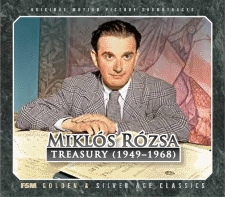

Quo Vadis was composer Miklós Rózsa’s first biblical epic film. In 1951, the man whose name would come to be so inextricably associated with togas, swords, crosses and such, had never scored any film set more than 200 years in the past (not counting the Arabian Nights fantasy The Thief of Bagdad). In fact, his strongest identification was with hard-hitting, modern-day film noir dramas, such as Double Indemnity and Brute Force. Nevertheless, the experience exposed a new vein of creativity in him, unleashing new modes (literally) and colors in his writing.

To control costs, Quo Vadis was to be made in Europe and the studio initially considered hiring a European composer. Managing Director L. K. Sidney asked for Rózsa’s advice on a list of potential names, some of whom were, in the composer’s opinion, “impossible.” One name, however, elicited Rózsa’s approval: he suggested that British composer William Walton, who had already scored several films (including First of the Few and Laurence Olivier’s Henry V) would be a good choice. Sidney, however, wanted to hire Rózsa, and although the composer modestly advised that Walton would be better, he was soon assigned to the film.

Once Rózsa started work on the picture, he decided to bring a certain “period authenticity” to the music. Beginning with an essay written by the film’s historical advisor on first century Roman culture (Hugh Gray, who also wrote the vocal texts that Rózsa set to music), the composer began an extensive musicological study. In an article published in the November–December 1951 issue of Film Music Notes, he detailed his point of view and his sources, which included the few known surviving fragments of ancient Greek music (since Roman culture was based on Greek models and no Roman music from the period of Quo Vadis has survived), plus Jewish melodies for the music of the early Christians. The scholar-composer obviously took great pride in being the first to care about making the music for a film set in ancient Rome match the era of the story, and although his imitation of period music was far from literal—and heavily filtered through his own musical sensibilities—it still provided the soundtrack a convincingly archaic sound remarkable for its time. Rózsa also supervised creation of the counterfeit onscreen instruments used in several scenes, basing the reconstructions on fairly abundant pictorial evidence from the period (pottery, statues, bas-reliefs, etc).

The first music Rózsa composed was the “source” music—the songs, dances and marches that would be performed on screen. Once those had been written and recorded, Rózsa was sent by director LeRoy to Rome to supervise filming of these sequences. His first trip to the Eternal City left a lasting impression and began a love affair with the locale that lasted the rest of his life. As a condition of his going to Rome, M-G-M required Rózsa to travel to London for a few days where the studio needed him to adapt some of Herbert Stothart’s themes from Mrs. Miniver (1942) for a sequel, The Miniver Story. On the train ride there and back, he passed through Rapallo, an Italian village where the Mediterranean vista quite took his breath away, and to which he vowed to return, as he did in the summer of 1953 (the first of many such summer holidays) to compose his Violin Concerto, Op. 24.

Unfortunately, Rózsa was soon recalled to Hollywood and had to leave Quo Vadis in the hands of a capable assistant, Marcus Dods, whom he had hired on the advice of Muir Mathieson. Once back in Hollywood, he was informed by Dods and choreographer Aurelio Miloss (of the Rome and La Scala opera houses) that their carefully planned “Bacchanale” scene had been scrapped by director LeRoy, replaced by shots of “a few limp showgirls.” The composer, trapped in Los Angeles, felt helpless to do anything that might rescue the scene and make his elaborate preparations pay off. Meanwhile, in order to avoid a last-minute rush, he wrote as much of the background score as he could while the cutting was in progress, aided greatly by supervising editor Margaret Booth.

Part of his task was to maintain some sort of compatibility between the Roman and early Christian music (which he based on historical models) and the dramatic underscore (which sings very much with his own voice). Christopher Palmer, in The Composer in Hollywood, argued that Rózsa succeeded in this task “partly in terms of the grounding of his music in Magyar folksong. For the roots of Hungarian peasant song are in the church modes and the pentatonic scale, its predominant intervals are the fourth and the fifth and therefore suggest a harmonic treatment derived from those intervals, i.e. superimposed chords of parallel fourths and fifths. Now these are precisely the means whereby an atmosphere of antiquity may be conjured up for western ears.”

When both film and score were finished, Rózsa returned to London, where he recorded the music with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and BBC Chorus. Some of the marches and choral numbers were recorded outdoors to achieve the proper acoustic (there are photos of both indoor and outdoor sessions in Double Life). It was a good experience for the composer, but things started to go downhill very soon after that. At the dubbing sessions, producer Sam Zimbalist (whom Rózsa considered a “dear personal friend”) constantly complained that the music was too loud. As a result, the music did not fare well in the finished film: it was often either drowned out by sound effects or mixed under dialogue at such a low level as to be virtually inaudible. The composer could take some consolation from the fact that MGM Records issued a soundtrack album at the time of the film’s release (both 45rpm and 78rpm 4-disc albums as well as a 10″ LP), thus allowing some of the music to be heard and appreciated apart from the film. There was also a 12″ LP of “dramatic highlights” on which some portions of the score could be heard. To salvage some of his finest work, Rózsa created a four-movement concert suite (extensively rewritten and developed to make a distinct orchestral work quite apart from the film cues), issued by Capitol Records in November 1953. In 1977, Rózsa revisited the score one last time, recording 45 minutes of highlights (again with the Royal Philharmonic), but once more he refashioned the original cues, making them more suitable for “concert” or in-home listening.

The music for Quo Vadis was recorded over a period spanning more than a year in four different sets of sessions on two continents. The first of these were pre-recordings made in April 1950, comprising songs and dances that would be used by the cast, the choreographer, the dancers and the director as a guide to learning, planning and filming. These have survived and offer a fascinating glimpse into the creative process. The following month a series of marches and fanfares were recorded (still prior to filming) with a wind ensemble at Culver City. After principal photography, the body of the choral/orchestral score was recorded with the Royal Philharmonic and BBC Chorus in London in April 1951. Unfortunately, the originals of these sessions were lost in a fire (the recording log bears the written notation: “destroyed by fire—entire show”); the tragic irony of this irreplaceable resource being consumed by “lambent flame” is inescapable. Two final sessions took place back in Culver City in August 1951, when a few minor modifications and additions to the score were recorded by the M-G-M studio orchestra, and fortunately these masters survive.

By combining the surviving music tracks (including those cues recorded in London employed on the soundtrack LP) with all usable music-and-effects tracks, FSM has been able to present a nearly complete chronological soundtrack, as well as a full CD of pre-recordings and bonus tracks, plus the original LP sequence. That so much trouble has been taken nearly 60 years after the music was written is both a reflection of the music’s enduring quality and a reward for the tenacity of the composer’s legion of admirers who have never given up hope for just such a release. (Cues that include sound effects are denoted below with an asterisk.)

Disc Three

- 1. Intermezzo

- This oddly named curtain-raiser (“Intermezzo” means “between halves” in Italian, suggesting that it was originally intended as an entr’acte) opens with an assertive French horn statement of the theme for Marcus Vinicius (Robert Taylor), but soon goes right to the heart of the score—the film’s love theme (“Lygia”). This original, modal tune (Rózsa himself called it “archaic”), dressed here in its fullest orchestral garb, is given a deeply impassioned treatment before ending quietly and contemplatively.

- 2. Prelude

- A brilliant imperial fanfare introduces the “Quo Vadis” theme, modeled on Gregorian chant, for chorus and orchestra. A post-production insert, recorded with the M-G-M studio orchestra in Culver City on August 16, 1951, allowed the choral entry to be delayed by two short phrases, perhaps so as not to overlap the film’s title card. Indeed, careful listening to the soundtrack of the recent DVD reveals that the new recording was actually laid over the London version, since the chorus can still be heard faintly during those few measures. The theme is given a muscular, almost militaristic development in which the Roman fanfares remain a forceful counterpoint.

- Drums (Appian Way)

- The opening narration is accompanied by onscreen drums as the returning Roman legions, led by Marcus Vinicius, march down the Appian Way toward the Eternal City. (A brief 0:13 cue was composed and recorded for the flashback to Calvary during this narration, but it was not used in the film and is consequently lost.)

- 3. Marcus’ Chariot*

- Marcus is told that he and his battle-weary troops must remain outside the city. Angered, he speeds off in his chariot. A short but impulsive development of his theme subsides as he enters the imperial palace.

- 4. Lygia*

- Temporarily billeted with retired General Aulus Plautius (Felix Aymler), Marcus meets Lygia (Deborah Kerr), named after the country of her birth (present-day Poland). She is a hostage of the state who was assigned to Plautius in her childhood and is now treated like a daughter by Plautius and his wife, Pomponia (Nora Swinburne). Marcus is immediately taken with her beauty, but his outspoken, rather brutish wooing does not impress her: “love” means very different things for the pagan Marcus and the Christian Lygia, and out of this difference arises the personal conflict in the drama. A simple statement of Marcus’ theme with harp and alto flute (suggesting cithara and aulos) leads to a relatively subdued version of the love theme, where soft woodwind colors alternate with warm strings. (Rózsa appears to have written and recorded a 1:48 cue [“Dinner Music”] for the ensuing dialogue scene, but the music was not used and is thus, like the “Calvary” cue, entirely lost).

- 5. Marcus and Lygia*

- A fragment of Marcus’ motive on clarinet yields to a new theme representing the faith of the early Christians as Lygia draws a fish (a symbol of Christianity) in the sand. Chant-like modal melodies and spare harmonization in open fourths and fifths lend the music an antiquarian and liturgical quality. This cue initiates a quasi-religious style that Rózsa developed further in several later scores (see, for example, the theme for John the Baptist from King of Kings and even the music for the “Trappist monks” in The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes). The love theme enters when Marcus returns to resume his wooing, highlighted by an ardent viola solo; when he presses his suit, the music abruptly becomes turbulent. Lygia escapes and Marcus’ pursuit is blocked by Ursus (Buddy Baer), Lygia’s bear-like guardian. A short transitional passage with bassoon and pizzicato basses underscores Marcus’ banter with Fabius (Norman Wooland), a fellow officer likewise billeted with General Plautius, about his encounter with Lygia.

- Preghiera* (“Prayer”)

- The theme of the Christians underscores Lygia’s prayer that Marcus will one day see the light of Christianity.

- Hymn of the Vestal Virgins

- Music was considered an essential part of Roman public ceremonies, so a number of set pieces, composed prior to filming, are associated with the celebration of Marcus’ military victory. A huge crowd has assembled to watch his triumphant procession through the city, and Rufia (Stresla Brown), the chief Vestal, presides over a pagan religious ceremony with dancers executing ritual movements to the music of an ecstatic chorus in honor of Vertumnus and Pomona, Roman gods of the fertility of field and garden. The words by Hugh Gray, difficult to distinguish on the soundtrack, are as follows:

- O guardian Nymph thou keeper of tree and soil,

The voice of love now clear in the garden calls.

He comes to thee who brings the harvest.

Open thy arms to embrace Vertumnus.

O guardian nymph, Vertumnus is calling thee.

Pomona, hear and answer thy lover’s plea,

See now he comes who brings the harvest.

Open thy arms to his love Pomona,

Pomona, Pomona, O goddess of earth. - 6. Hail Nero March

- A petulant Nero (Peter Ustinov) is persuaded to greet the impatient crowd. He signals the onscreen brass players to begin their antiphonal fanfare (how marvelous it would have been in stereo!) and the first of Rózsa’s many Roman marches is heard as Marcus parades before the emperor. The onscreen drums are perfectly synched to the pre-recorded track, and the reconstructions of Roman brass instruments, including salpinx (a very long trumpet-like instrument with a bulb or bell on the end), buccina (forerunners of the modern French horn) and aulos (double flute, possibly with reeds), are convincingly simulated by rough-sounding contemporary equivalents. The martial theme, which will become associated with Nero, evokes the pride and arrogance of Imperial Rome. When Marcus enters on his chariot, his theme, blared on trumpets, becomes the “B” section of this traditional three-part march form.

- 7. Eunice*

- Marcus’ uncle Petronius (Leo Genn) is Nero’s dispassionate counselor and a master of prevarication. He introduces Marcus to one of his slaves, Eunice (Marina Berti), whom he intends to give to his nephew as a gift. Marcus, fixated on Lygia, is uninterested in the slave girl. After being dismissed, she reveals her unspoken love for Petronius to an implacable marble bust of her master. Her theme, introduced on harp, is based on the first Ode of Pindar found in Sicily in 1650 but dating back nearly 2,000 years earlier.

- The Hostage*

- Unrequited love of a different sort is underscored by the love theme as Lygia passes by the symbolic fish in the garden, which Marcus had angrily scratched out. An unexpected knock on the door signals the arrival of Roman troops sent by Nero on Marcus’ behalf to bring “the hostage” Lygia to the palace. The music takes an abrupt turn to darkness as Rózsa reverts to his film noir style for a brief moment of tension.

- 8. The Banquet of Nero—Roman Bacchanale

- The next four tracks comprise the “entertainment” at a party hosted by Nero in honor of Marcus. Lygia is escorted into the banquet hall, where dancers (a satyr and a group of nymphs) move among the guests in a rather chaotic scene. The wild and decadent opening (allegro molto e frenetico in 5/8 time) is based on a second century fragment, while a contrasting, calmer midsection plays beneath Marcus’ continuing wrong-footed pursuit of the reluctant Lygia. The first theme returns and is succeeded in turn by a third melody, derived from the ancient Greek “Hymn to the Muse.” This final section (beginning at 2:16) was not used in the film.

- 9. Syrian Dance

- A lone female dancer entertains the emperor and his guests. The English horn solo at the beginning prefigures a similar opening to “Salome’s Dance” in King of Kings. This exotic miniature (marked allegretto orientale) stands in a long tradition of pseudo-orientalisims that includes examples by Camille Saint-Saëns, Richard Strauss and many others.

- 10. The Burning of Troy

- Nero is persuaded to sing for his guests, and he “honors” them with a performance of this song, on which he had been working earlier in the film but which he now pretends to extemporize. He accompanies himself on a lyre (simulated by a clarsach, or small Scottish harp), an authentic touch since the historical Nero did indeed play a type of lyre known as the cithara. The melody is derived from a roughly contemporaneous fragment of a Greek drinking song, the Skolion of Seikilos, and the subject matter of the song eerily prefigures the burning of Rome.

- 11. Siciliana Antiqua*

- As the party continues, Nero reveals to Lygia that he has given her as a reward to Marcus. A less frenzied counterpart to the “Syrian Dance” accompanies the scene, unmindful of the turbulent human emotions playing out on screen. The opening motive of this cue is derived from the oldest extant Sicilian melody (yet one with a pronounced Arab flavor). The middle section simulates the drone and chanting of a bagpipe—one of Nero’s favorite instruments—which Rózsa also evoked in some of his concert music (Kaleidoscope, Three Hungarian Sketches, Piano Sonata, etc.). When the opening returns, it is ornamented with additional counterpoint. The music extends beyond the banquet scene to cover a short exchange between Lygia and Nero’s devoted slave Acte (Rosalie Crutchley), in which the latter reveals that she is a Christian sympathizer.

- 12. Escape*

- Dark murmurings from the depths of the orchestra accompany Lygia as her litter is carried through the city while Ursus lurks in the shadows. A brief agitated scherzo erupts when he attacks the litter-bearers and rescues Lygia from her captors. A terse variant of Marcus’ theme accompanies the nervous pacing of Plautius as he awaits news of the rescue, but instead he is greeted by Marcus’ impatient knock—the commander has come to reclaim Lygia.

- 13. Petronius and Eunice*

- For all his vaunted wit and wisdom, Petronius seems surprisingly ignorant of the adoring love of his slave, Eunice. Bemused by Marcus’ fixation on Lygia, Petronius asks Eunice about love, and gleans from her reply that he himself might be the object of her affections. Her theme is followed by the introduction of his—a gentle, noble melody in the Aeolian mode, eloquently sung by the string choir with decorative woodwind figurations. It rises to a passionate climax as Eunice excitedly prepares to travel with Petronius to Antium.

- 14. Chilo*

- In his search for the Christians who are harboring Lygia, Marcus consults with Chilo (John Ruddock), an old soothsayer. A subdued version of the “Quo Vadis” theme is heard while the disreputable Greek explains the meaning of the fish symbol; an icy, sul ponticelli string passage (at 1:05) underscores his promise to lead Marcus to the grotto where the forbidden sect meets in secret.

- 15. Jesu Lord

- Marcus watches from the shadows as Paul (Abraham Sofaer) baptizes the most recent Christian converts. Nothing could be further from the exotic music heard at the banquet than this sparse unison vocal set piece, where the people respond to the priest in an antiphonal form still preserved in today’s church. The melody, of Yemenite Jewish origin, dates as far back as the Babylonian captivity but was eventually incorporated into the body of Gregorian chant as a Kyrie.

- 16. Resurrection Hymn

- Rózsa used a Greek model (the “Hymn to Nemesis,” written by the lyric poet Mesomedes of Crete in the second century A.D.) for this affirmative unison hymn begun by a solo voice— and eventually taken up by the full assembly—after a sermon by Peter (Finlay Currie).

- 17. Vae Victis* (“Woe to the Conquered”)

- Marcus, Chilo and their gladiator bodyguard follow Lygia as she returns home. Ursus blocks their way, and in the struggle he kills the bodyguard. Typical Rózsa fight music with heavy accents accompanies the scene, building until Ursus throws the bodyguard over a wall; he then bears the wounded Marcus to the house of Plautius.

- Caritas* (“Charity”)

- Lygia cares for Marcus’ wounds in an act of Christian charity. His usually martial theme appears here in a tender, almost pastoral, version against a gentle woodwind ostinato. This subtle musical transformation perhaps anticipates a similar transformation in Marcus’ character.

- 18. Mea Culpa* (“My Fault”)

- Marcus awakes and takes in his unfamiliar surroundings. His theme returns on celli, against a mournful sighing motive in the violins and violas. The music builds to an impassioned climax when he sees Lygia, and the keening semitones move into the bass register (bassoons) as she brings Ursus to him: her bodyguard wishes to apologize for killing the commander’s friend.

- 19. Non Omnia Vincit Amor* (“Love Does NOT Conquer All”)

- Marcus, who does not understand Ursus’ attitude, admits defeat and sets Lygia free. She responds by falling into his arms and acknowledging her love for him, but as far as he is concerned, her Christian faith still stands in their way. A joyous harp introduction leads to the love theme, but a full resolution is kept at bay, and a sad, almost desolate development of the “Quo Vadis” theme rounds off the cue.

- 20. Temptation

- Paul tries to explain to Marcus what he must do to accept Christ and become worthy of Lygia’s love, but without success. The Roman Marcus simply cannot understand: “What sort of love is it that acknowledges a force greater than itself?” he asks. Lygia sadly decides not to come with him, and he leaves in anger. Paul reassures the heartbroken Lygia that even Christ was tempted by evil, and that the strength of her faith will win the day. A slow, resigned development of both Marcus’ and Lygia’s themes concludes with a sorrowing solo cello.

- Eunice’s Song at Antium*

- Nero has moved the court to Antium. Marcus and Petronius play chess while Eunice sings a song derived from her theme (“Invocation to Venus,” with text by Hugh Gray) and accompanies herself on a lyre, again suggested by a Scottish harp. Most of the music plays under Nero’s discussion with his architect about his plan for a new Rome, adding a certain level of detached irony to the scene.

- 21. Petronius’ Presentiment*

- Petronius reveals his misgivings about Nero to Eunice. Mysterious phrases evolved from Eunice’s song are rounded off by an unclouded string statement of her theme, as she declares her undying love for Petronius.

- The Women’s Quarters of Nero*

- Marcus is summoned to see Nero’s wife, Poppaea (Patricia Laffan), in her quarters. She taunts him for his love of Lygia, but when he assures her that he is no longer interested in the Christian girl, she makes her own move for his attention. A bit of source music performed by a small ensemble with prominent woodwind solos plays innocently in the background of this seduction scene. The second theme of this ternary piece would be echoed by Rózsa in his score for Ben-Hur, during Arrius’ party.

- 22. Chariot Chase*

- Nero announces to the stunned court that in order to create a new Rome (which will be called “Neropolis”) he has set fire to the old one. Horrified, Marcus realizes that Lygia is in great danger, and he races off in his chariot to rescue her (thus revealing his true feelings for her). A jealous Poppaea orders troops to follow and stop him, and the resulting chariot chase echoes the famous race in M-G-M’s 1926 silent film of Ben-Hur. When Rózsa scored the remake of that film almost a decade later, he would leave the chariot race without music. For Quo Vadis, however, he provided an exciting orchestral tour-de-force—one hopelessly buried under the sound effects of horses’ hooves, cracking whips and grinding wheels in the film. (Interestingly, Rózsa added percussion effects simulating the first two of these when he recorded highlights from the score in 1977!) Fortunately, the LP track has preserved most of this music. After a fretful introduction based on the ancient Greek “Hymn to the Sun,” a relentless, galloping rhythm supports fragments of the “Quo Vadis” theme that chase each other through the brass section of the orchestra. A contrasting middle section changes the underlying rhythm, alternating a fanfare-like idea with stabbing string phrases, the “Quo Vadis” theme returning as the chase hurls to its headlong conclusion and ends with fragments of Marcus’ theme and a final peroration on “Quo Vadis, Domine?” Rózsa reprises the “Hymn to the Sun” theme as Marcus enters the burning city, but that portion of the cue is not included here (since it is hopelessly covered by sound effects).

- 23. The Burning of Rome (Nero’s Fire Song)*

- Popular legend has it that “Nero fiddled while Rome burned,” but musical historians know that there were no fiddles in ancient Rome—it is thus more likely that Nero sang and accompanied himself on the lyre. In fact, near-contemporary chroniclers reported that Nero sang the “Sack of Ilium” in stage costume while the city burned. In Quo Vadis, Peter Ustinov sings “The Burning of Rome,” written by Rózsa and Gray, while flames consume the city and Petronius, Poppaea and others look on in horror. This film version of the song is shorter than either of the pre-production versions (see disc 4, tracks 14, 15 and 22) and Ustinov’s painful vocal is more barked than sung.

- 24. Tu es Petrus* (“Thou art Peter”)

- Against Petronius’ advice, Nero decides to blame the burning of Rome on the Christians. At the home of Plautius, Marcus and Lygia meet and are reconciled, but he cannot “turn the other cheek”—he feels Nero must be stopped. As he leaves to meet with Petronius and other like-minded citizens, Peter greets him and thanks him for all he has done. Peter also comforts Nazarius (Peter Miles), a young boy who is traveling with him to meet Paul in Greece. A subdued version of the love theme accompanies the parting of the lovers. Calmer, liturgical phrases derived from “Jesu Lord” and featuring a solo cello reflect Peter’s saintliness and wisdom.

- Meditation of Petronius

- Horrified by Nero’s actions, Petronius expresses deep regret that he remained a cynical onlooker rather than trying to stop his emperor. The nobility of his theme is infused with sadness by a slow tempo and subdued dynamics.

- 25. Petronius’ Decision*

- Marcus arrives with a petition asking General Galba to return from Tuscany and replace Nero as emperor. Petronius gladly signs it because he knows he is already a marked man. He hints to Eunice that he has a strategy to frustrate Nero’s plans to execute him. A somber clarinet solo picks up his theme, which is brought to a resigned conclusion by low string phrases.

- 26. The Vision of Peter*

- As Peter and Nazarius are on their way to join Paul in Greece, Peter becomes troubled by a feeling that something is wrong. Suddenly, he sees a vision of light, and Nazarius unknowingly speaks the words of the Lord (against a sustained organ chord) instructing Peter to return to Rome to help His people. Mystic, open chords with string harmonics hang suspended in the air while woodwinds, muted brass and a mystic choir of female voices intone the “Quo Vadis” theme.

- Petronius’ Banquet Music*

- Petronius has invited a few of his steadfast friends to a dinner to bid them farewell. His theme is transformed into a bit of source music with woodwinds and subtle percussion.

- 27. Petronius’ Death (Parts 1 and 2)

- In front of his guests, Petronius frees Eunice and makes her his heir, then calls for a physician to slash his wrist. Horrified, Eunice tries to stop him, but without success. Not willing to part from him, she takes the knife and cuts her own wrist. Over a typical Rózsa rhythmic ostinato painful, despairing string phrases developed from her theme underscore her declaration of undying love. The music ceases briefly while the dying Petronius dictates a final letter to Nero, rife with sarcasm and honesty at last. Then his theme resumes with the sighing motive first heard in “Mea Culpa” (track 18), expressing mournful sadness at the loss of so great a Roman. (There is a small edit in the film cue, so this track from the LP is a bit longer than what is heard in the film.)

- 28. Ave Caesar (“Hail Caesar”)

- A bloodthirsty crowd has assembled in the arena to witness the spectacle of the falsely accused Christians being fed to lions. A new Roman march helps establish an almost festive atmosphere while proving that the inexorable might of Roman power cannot (yet) be stopped.

- 29. Aftermath*

- Numerous fanfares (see disc 4, tracks 35–45) add official pomp to the execution of the Christians, which they counter with the singing of the “Resurrection Hymn” (see track 16). At the end of the day’s horrible events, Nero walks among the victims’ bodies strewn throughout the arena, looking for clues to their joy in the face of such pain. Celli and basses intone the hymn, with mocking semitones from muted brass.

- 30. Hymen* (“Marriage”)

- Marcus, arrested as a Christian sympathizer, is united with Lygia in prison. Awaiting execution, they ask Peter to marry them. As he gives them his blessing, quiet woodwind fragments of the “Quo Vadis” theme lead to an exquisite treatment of the love theme featuring solo viola and later a plangent oboe on a bed of quiet strings. Two passages for high strings (the second based on the love theme) are separated by a variant of “Jesu Lord,” eventually bringing the cue to a resigned but peaceful conclusion.

- 31. Ecce Homo Petrus* (“Behold the Man Peter”)

- Peter is taken to Vatican Hill to be crucified; the mocking semitones from “Aftermath” are heard echoing each other in a short passage that calls to mind Bernard Herrmann. A chant-like phrase (which prefigures the “Mount Galilee” theme from King of Kings) builds to a massive orchestral/choral climax as the camera pans to a shot of Peter, crucified upside-down at his own request because he did not feel worthy of suffering the same fate as his Savior. The second day of executions, this time by crucifixion and burning, is met with further hymn singing (not included on this CD because it is mostly covered by the sound of crackling flames).

- 32. Finis Poppaea (“Poppaea’s End”)

- Poppaea has planned a special fate for her rival: Lygia is to be the victim of a raging bull, although first the animal will have to kill her protector, Ursus. Poppaea has Marcus brought to Nero’s reviewing stand to watch the executions. The emperor improvises a short song (not on this disc) to mock both Marcus and the specter of Petronius. To Poppaea’s amazement, Ursus manages to kill the bull, and the crowd demands that Lygia be set free. When Nero refuses, pandemonium ensues. Marcus further enflames the crowd by announcing that it was Nero who burned their beloved city and that General Galba approaches Rome at that very moment to become their new emperor. Nero flees in panic as the mob attacks the palace. A funereal tread and mocking echoes of Nero’s march, his fanfares and his song on the burning of Troy haunt him as he mounts his throne. He sees Poppaea and—blaming her for turning his people against him—strangles her. The orchestral tension explodes in a moment of sheer terror, highlighted by string trills and xylophone accents. Nero tries to run away but continues to be pursued by his themes. Acte steps out of the shadows, eerily framed by further trills and muted brass.

- 33. Nero’s Suicide*

- Acte performs one final service for Nero: she helps him to die “like an emperor” by his own hand. Unsettled somber strings and low brass and winds develop Nero’s themes; phantom harp accents recall his lyre (which falls next to his body as he dies).

- Galba’s March

- One final Roman march (which Rózsa would reuse in Ben-Hur) celebrates Galba’s entry into the city. (In the film, the music abruptly cuts off as the next scene begins; this track presents the complete version.)

- Finale*

- A woodwind development of the love theme over harp arpeggios introduces a ray of light as Marcus, Lygia and Nazarius travel from Rome, pausing briefly at the spot where Peter had his vision. The shimmering chords from that cue (track 26) lead to the final choral apotheosis on the “Quo Vadis” theme, sung triumphantly over the end cast.

- 34. Epilogue

- Rózsa gives his love theme one last impassioned, string-based run-through as the audience leaves the theater. Soaring trumpets and pealing chimes bring the entire score to a jubilant conclusion. —