Kind Lady

Kind Lady (1951) stars Ethel Barrymore as wealthy Mary Herries, an elderly woman living in turn-of-the-century London with her maid and cook, in a home filled with valuable artworks by the likes of Rembrandt and El Greco. The house’s ornate doorknocker, the work of Benvenuto Cellini, catches the eye of Henry Elcott (Maurice Evans), a struggling artist with a baby and a frail wife, Ada (Betsy Blair). Mary is charmed by Elcott and impressed by his knowledge of art, and maintains contact with him even after he steals her valuable cigarette case—he eventually returns it to her after pawning it to buy painting supplies. Henry brings Ada and the baby for a visit but when Ada falls unconscious, Mary insists on letting the ailing woman recover in her house. Soon Elcott is treating Mary’s home as his own. After the cook quits in protest, Elcott invites his friends, Mr. and Mrs. Edwards (Keenan Wynn and Angela Lansbury), to visit. Her suspicions about Elcott growing, Mary tries to kick the visitors out of her house but finds herself a prisoner in her own home: she and her maid, Rose (Doris Lloyd), are kept locked in their rooms. While the Edwardses pretend to be butler and maid, Elcott poses as Mary’s nephew, proceeding to sell her valuable possessions and telling all visitors that his “aunt” has become mentally ill. Mary resists signing her power of attorney over to Elcott despite his threats, and tries to convince Ada to help her while turning Mrs. Edwards against Elcott. Rose escapes from her room, but is murdered by Edwards before she can flee the house. Elcott sends Edwards up to Mary’s darkened room to tip the captive out of her wheelchair and through an open window, the body falling to the street in an apparent suicide—but the body turns out to be Rose, her corpse placed in the chair by Mary and Ada, and Elcott and the Edwardses are arrested.

Kind Lady’s story of a generous woman and her charming but dangerous visitor was remarkably popular throughout the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s. It began as the short story “The Silver Mask” by Hugh Walpole, first published in the March 1932 issue of Harper’s Bazaar, one of many novels and stories he wrote about the Herries family. Edward Chodorov adapted the story as a stage play, which opened on Broadway on April 23, 1935, with Grace George as Mary and Henry Daniell as the villain. The first film version saw release in December of that year, with George B. Seitz directing, and Aline McMahon and Basil Rathbone in the leads. Grace George reprised her role for a Broadway revival in 1940, with Stanio Braggiotti taking over the role of the villain. Two productions of Kind Lady were mounted for television: Fay Bainter starred in a 1949 production on The Ford Theatre Hour and Sylvia Sidney in a 1953 episode of Broadway Television Theatre. The play, which is set entirely in Mary’s living room, was also a perennial favorite of amateur theater groups.

The screenplay for the 1951 remake of Kind Lady was credited to Chodorov as well as Jerry Davis (who later had a prolific career in TV as a writer-producer) and former Hitchcock collaborator Charles Bennett (The Man Who Knew Too Much, Secret Agent, Sabotage). Their script made significant changes to the material: the character of Peter, the fiancé of Mary’s niece, was dropped entirely, and his role in investigating Mary’s plight was given to Foster, Mary’s banker. The murder of Rose was moved to much later in the story (originally she was killed soon after Henry and his accomplices took over the house) and the climactic sequence, where Ada and Mary substitute Rose’s corpse for Mary, was a major addition.

Director John Sturges is remembered today for his widescreen stories of men in conflict, often in spectacular outdoor settings: Spencer Tracy facing the residents of an unfriendly desert town in Bad Day at Black Rock, the Magnificent Seven riding across the Mexican countryside, Steve McQueen escaping the Nazis by motorcycle in The Great Escape. It is thus something of a shock to see Sturges helming a stage-based, black-and-white thriller about an elderly woman menaced in her own home, but in his early career Sturges worked in a wide variety of genres. While the film lacks the visual scope of Sturges’s more famous adventure efforts, his confident direction helps take the curse off the stagebound nature of the story, and his subtle camera movements add to the tension of the finale. The casting of the 71-year-old Barrymore—much older than previous actresses who had taken on the role—adds to her vulnerability, and the sinister way Maurice Evans pushes a wheelchair across a room is more menacing than a brandished gun.

Kind Lady provided Ethel Barrymore one of her last leading roles, and she handled the part with commendable authority and understatement (although filming was halted for a month when the star fell ill). Many of the supporting cast played roles that evoke their work in more famous films: Evans played the ill-fated friend of another woman-in-jeopardy, Mia Farrow in Rosemary’s Baby, 17 years later, which gives his role as a captor in Kind Lady (his first Hollywood film) unexpected resonance; John Williams’s inquisitive banker serves as a dry run for his helpful Scotland Yard inspector in Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder three years later; and Angela Lansbury’s typically witty work as a Cockney accomplice serves as enjoyable transitional point between her saucy maid in Gaslight and her indelible stage performance as the cheerfully murderous Mrs. Lovett in Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd. Kind Lady earned an Oscar nomination for Walter Plunkett and Gile Steele’s costumes, while the film’s release provoked a minor bit of controversy, as the “Wage Earners Committee” picketed the film’s L.A. screenings due to the participation of Chodorov, who had been named as a communist in the HUAC hearings. M-G-M managed to defuse the situation by insisting that Chodorov (despite his shared screenplay credit) had not been involved since the studio had purchased the rights to his play years earlier, and that he would receive no royalties from the film.

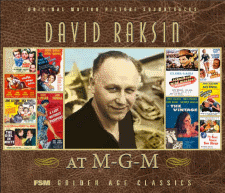

Kind Lady is one of four films directed by John Sturges and scored by David Raksin at M-G-M in the early ’50s (the others being Right Cross, The Magnificent Yankee and The Girl in White, all represented in this set). Kind Lady begins as a seemingly mild character drama about the relationship between a wealthy woman and a struggling artist before transforming into a moody thriller, and Raksin’s score emphasizes this switch in tones. The film takes place over the Christmas holiday season, so the composer begins his main title with a reworking of “Joy to the World” before segueing to his theme for Mary, a fittingly warm (but never cloying) melody that offers no hint of the menace to come. Mary’s theme dominates the early part of the score just as Mary dominates the story, but once Elcott’s evil side is finally revealed (in a cue titled, fittingly enough, “Elcott Revealed”), Raksin introduces a new theme, dominated by a four-note motive, which subtly and elegantly expresses Elcott’s sinister nature. Director Sturges keeps the murder of Rose just off screen, with Raksin providing violent music for the killing, and some of the suspense cues call to mind another Raksin woman-in-jeopardy score, What’s the Matter With Helen? (1971). Once order is restored and Mary is again the mistress of her house, Raksin reprises her theme for the end titles. —

David Raksin’s complete score to Kind Lady is presented on this collection in monaural sound from ¼″ tapes derived from 35mm optical masters, with a few (otherwise lost) cues transferred from acetate discs. The film’s source music was not composed by Raksin and is not included here.

- 1. Main Title

- A festive introduction for brass and strings announces the M-G-M logo and establishes the story’s Christmastime setting. The opening titles play out over a moodily lit London street to the accompaniment of the main theme, an elegant, compound-meter melody for Mary Herries (Ethel Barrymore). The theme ends just as a group of carolers gather across the street from Herries’s home singing “God Rest You, Merry Gentlemen” (not presented on the CD).

- 2. Miss Herries and Mr. Elcott

- Mary’s initial meeting with Henry Springer Elcott (Maurice Evans) is unscored: he rings the bell at her home and inquires about her ornate Italian doorknocker. Once he bids her farewell, she returns to the drawing room and finishes conducting business with her new banker, Mr. Foster (John Williams). A warm setting of Mary’s theme marks a transition to a new day: Mary is dropped off at home by her niece, Lucy (Sally Cooper), and she notices Elcott standing in a courtyard across the street, painting a picture of her home. She exchanges pleasantries with him, her them continuing underneath their dialogue; he offers to bring more of his paintings by for her to see, and she accepts. The film again jumps ahead in time to her next encounter with the artist (the music continuing during the transition). At her front window, she watches Elcott approaching; Raksin introduces for him a deceptively benign and dignified melody on oboe, then reprises Mary’s theme as her maid, Rose (Doris Lloyd), admits him to the house.

- 3. Cigarette Case

- Elcott presents his paintings to Mary but his eventual exit from her home is awkward and abrupt. The score underlines her concern—she notices that her expensive cigarette case is suddenly missing. A simple-meter rendition of her theme plays for yet another segue: Mary’s chauffeur drives her to a bookstore, with the increasingly shady Elcott following behind on foot. Raksin continues to develop the melody as Mary shops, until an apparently guilt-ridden Elcott enters the store and returns her stolen cigarette case.

- 4. No Offense, Miss Herries

- Elcott invites Mary to his flat to see the rest of his work. His meager, chilly living space prompts her to express concern for his family, and he takes offense. As she excuses herself to leave, the score responds with a brief, plaintive passage for woodwinds, yielding to Mary’s theme as she later writes an apology letter that is delivered to Elcott. The note contains money so that he can buy warm clothes for his wife, Ada (Betsy Blair).

- 5. Elcott Plays a Pawn

- Ada collapses while waiting outside and Mary takes in the Elcott family after a passing doctor (Victor Wood) diagnoses her with pneumonia; Henry carries his wife upstairs to the accompaniment of distraught strings. Time passes and the scene transitions to Mary’s bedroom; an inquisitive development of the main theme plays as Lucy examines a portrait that Elcott is painting of her aunt. Warm writing follows for Mary telling her niece about her friendship with Elcott, with the painter’s dignified melody sounding when he pops in and out to provide an update on Ada’s health. Mary’s theme rounds out the cue as Lucy departs and observes Elcott escorting the doctor to Mary’s room.

- 6. The Plot Thickens

- Elcott agrees to look for a job while his wife recovers, but suspicious material for woodwinds and strings underscores the painter’s dismissal of the doctor after they privately discuss their “arrangement.” Time passes and Mary checks in on the bedridden Ada, the compassionate main theme mingling with a bittersweet line for oboe developed out of the opening material from “Cigarette Case.” Mary comments that the doctor has not stopped by recently, but Ada lies, assuring her otherwise. The scene segues to Elcott arriving home and accepting a letter from the mailman; the main theme begins to show signs of strain as Mary silently observes the painter perusing her mail and bossing around Rose.

- 7. Elcott Revealed

- Mary is pushed to her breaking point when Elcott allows the creepy Edwards family (Keenan Wynn, Angela Lansbury and Sherlee Collier) to visit their “friend” Ada—in reality, Ada barely knows them. A sinister motive (first suggested in “Cigarette Case”) is introduced on bass clarinet for Elcott the invader, replacing his original harmless tune as he and the Edwardses surround Mary and threaten her: it becomes clear to the old woman that she is a hostage in her own home. The opening pitches of the main theme emerge out of the dread-ridden material as she commands them all to leave, but Elcott irrationally insists that she pay him for his services—his “weeks of planning.” As Mrs. Edwards prepares to restrain Mary, Mr. Edwards sneaks downstairs accompanied by cautious string writing while an unsuspecting Rose telephones a nursing home to arrange a room for Ada.

- Mrs. Edwards

- Hollow woodwinds sound as Mrs. Edwards finishes tying Mary to her bed, while disturbed suggestions of the main theme give weight to Elcott’s smug implications that there will be no escape for the old woman. Downstairs, Mr. Edwards informs Elcott that Rose has phoned for an ambulance for Ada; string-based tension builds as Elcott stares down Rose. Mrs. Edwards subsequently phones the nursing home to cancel the request and the villains lock Rose in her room.

- 8. The Note

- Elcott begins to sell off Mary’s valuable furniture and paintings. When an art dealer, Monsieur Malaquaise (Henri Lentondal), arrives to look over the remaining pieces, Mary is deliberately left alone with him in the drawing room. She attempts to alert him of her dilemma by slipping him a note; the invader motive is reprised on bassoon once Elcott returns and escorts Malaquaise to the front door. Malaquaise uncomfortably hands Mary’s note over to Elcott, who has already informed the dealer of her “dementia.” The score underlines the futility of Mary’s effort with desperate solo violin and woodwinds as Elcott returns the note to her. A chordal “death” motive for strings bleeds over to a subsequent shot of a wheelchair being delivered to the home. Moody underscoring plays through a transition to Mary’s room, where Elcott continues to paint his captive’s portrait.

- 9. The Portrait

- The invader motive introduces a scene in which Mary gently interrogates Ada and learns that Mr. Edwards holds the key to Rose’s room. The score sets a mysterious mood with material based on the same motive for Mary’s request to see an old portrait Elcott painted of Ada, one that might explain the crazed artist’s past.

- Downstairs, Rose’s sister and brother-in-law, the Harkleys (Moyna MacGill and Barry Bernard), have arrived. Elcott has already told them that Rose has run off with a married man and he gives them her wages to throw off any further suspicion. An interjection of playful material bounces along for the couple leaving the house—Mrs. Harkley wants to involve the police (to find Rose) but her husband is satisfied with the explanation and the money.

- The score takes on a contemplative tone as Elcott returns to Mary’s room and explains how he has dealt with the Harkleys. When he reveals his nearly completed portrait of Mary—a haggard, practically demonic representation of the kind lady gazing at herself in a mirror—the score responds with a shimmering, frightful rendition of the invader motive. Mary dismisses the painting—and Elcott himself—as “corrupt, vicious and insane,” the invader idea diminishing fatefully as he rejects the insult.

- 10. Foster Again

- Foster, the banker, arrives for an appointment with Elcott. Tense variations on the invader motive and Mary’s theme sound as Mr. Edwards admits the banker and informs Elcott of his presence. As soon as Elcott leaves Mary alone, she attempts to break free of her constraints, to the determined chattering of muted brass. The cue continues with a lush but suspicious quality as Elcott escorts his guest into the drawing room; Elcott wants to sell the house, but first Foster and the bank require proof of Mary’s insanity.

- 11. Portrait of Ada

- Mary gives Mrs. Edwards a hidden stash of money in exchange for the key to Rose’s room. When Mrs. Edwards presents her husband with the cash and suggests that they leave before Elcott can give them their cut of his profits, he slaps her; she retreats, to a rush of agitated strings and brass.

- Tentative underscoring follows for a scene in which Ada brings Mary the portrait she requested. The cue reprises the death motive from “The Note” for Mary discovering Ada’s corpse hidden in the background of the painting—she deduces that Ada is Elcott’s prisoner, not unlike herself. The score quietly plays up Ada’s internal conflict as she confesses that she has remained with Elcott out of fear for herself and her baby. She also gently reveals that Elcott has murdered a woman in France, one whose portrait he painted. Mary implores Ada to help Rose and gives her the key to Rose’s room; once she leaves, Mary wipes some paint off the corner of the picture, revealing the name “Ashmond,” Elcott’s alias. The shimmering rendition of the invader motive from “The Portrait” is reiterated, tying the scene back to the reveal of Elcott’s painting of Mary.

- Rose Goes

- Ada releases Rose from her room; coy developments of the death motive and the main theme play as Mr. Edwards catches her attempting to escape and sneaks up the stairs toward her. She makes eye contact with him and an exclamatory brass version of the death motive cries out before he murders her off screen.

- 12. Checkmate

- With Foster on his way to the house, Elcott positions Mary in her wheelchair in front of an open window. Austere renditions of the main theme and the invader motive underscore the latter half of his subsequent conversation with Mr. Edwards: he lies, telling him that Mary knows he killed Rose and that he must kill her too before Foster arrives—and it must look like a suicide. Ada overhears the plan and rushes to inform Mary.

- The score layers suspense over a gnarled ostinato that plays through the film’s climax: outside, a suspicious Foster sends a constable across the street to Mary’s house; in the drawing room, Elcott destroys the incriminating portrait of Ada; Mr. Edwards proceeds into Mary’s room, moves toward the wheelchair and dumps its inhabitant onto the street below, accompanied by an outburst of brass and strings. A crowd gathers around the body to agitated variations on the invader motive, which continue as the villains return downstairs to answer the front door. They are shocked when Mary and Ada emerge from the drawing room, Elcott instantly deducing that it was Rose’s corpse that was dropped out the window. A final, distraught rendition of the invader theme sounds as Mary walks past the ruined mastermind and opens the door to admit Foster and a pair of constables.

- End Title and Cast

- Mary gazes at her decadent doorknocker—which helped instigate her nightmare—and closes the door, the score reprising the jovial introductory material from the “Main Title.” A final reading of Mary’s theme plays through the cast listing to conclude the score. —