The Asphalt Jungle

In the classic film noir The Asphalt Jungle (1950), a team of criminals carries out a jewel heist only to face devastating punishment when their plans spiral out of control. Directed by John Huston (who, with Ben Maddow, adapted W.R. Burnett’s novel) the naturalistic thriller plays out in a nameless, crime-ravaged city, whose police force makes life increasingly difficult for crooks and the women who suffer by their sides.

Chief among the jewel thieves are: Sterling Hayden as Dix, a tough-guy “hooligan” and compulsive gambler who idly dreams of buying back his family’s horse farm in Kentucky; Oscar-nominated Sam Jaffe as “Doc” Riedenschneider, the immigrant criminal mastermind who hatches the idea for the robbery; and Louis Calhern as Alonso Emmerich, a desperate, bankrupt lawyer who borrows cash to finance the robbery, with plans of double-crossing his partners after the jewels are stolen. While the heist is carefully conceived and executed, a series of fateful mishaps—and Emmerich’s betrayal—hinder plans to fence the stolen property. Each criminal ultimately succumbs to a personal inner weakness that leads him to either jail or death.

The film’s thieves and murderers are never glorified, but rather depicted as flawed and desperate, a pathetic collection of outcasts trapped in their respective lots in life. In contrast to the police—who are contemptibly drawn as either corrupt or ruthless opportunists—the crooks are colored with touches of humanity, be it Dix’s longing to reconnect with his innocent, youthful days on his old farm, or in one criminal’s unexpected, impassioned defense of a stray cat. While Dix and Doc form a mutual bond that sets them apart from the traitorous Emmerich, their code of honor can neither redeem them nor save them from the fates that slowly tighten around them as the film drives towards its dreary conclusion. Perhaps even more overtly tragic are the naïve female characters, particularly Emmerich’s neglected, sickly wife, May (Dorothy Tree), who clings to happy memories while her husband dreams of escaping with his gorgeous, but similarly oblivious mistress, Angela (Marilyn Monroe, in a brief but important role early in her career).

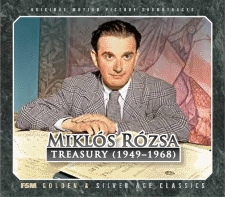

Filmed in oppressive black and white by Oscar-nominated cinematographer Harold Rosson, The Asphalt Jungle benefits from a realistic atmosphere furthered by a noticeable lack of music. The film’s scant score by Miklós Rózsa—consisting only of a main and end title—was the last of the composer’s film noir period, which yielded such beautifully ominous classics as Double Indemnity (1944), The Killers (1946) and Brute Force (1947). Rózsa’s rich, modal style was groundbreaking in the Oscar-nominated score for Double Indemnity, where the pervasive main theme was inexorably linked to the narration of the ruined main character, scoring the picture from his point of view and offering a dark musical depiction of his psyche. Rózsa’s work on The Asphalt Jungle offers something of an environmental bookend, mirroring the film’s title during the opening credits by painting the nameless city with dangerous, percussive rhythms as well as a suitably exotic melody. This did not represent the composer’s first approach, however. In his autobiography, Double Life, Rózsa recalled: “I wrote the prelude and asked Huston to come and hear it. He didn’t like it. He said it was doing what innumerable preludes had done already, telling the audience that what they were going to see was supercolossal, tremendous, fantastic, the greatest picture of all time; and then came—just a picture. What he wanted was a tense but quiet opening, and that is what the picture has now.”

Aside from a handful of source cues (located at the very beginning and end of the picture), the body of the film is entirely unscored. The characters are narratively “stranded,” deprived of any musical groundings that might help an audience interpret the story—even the heist centerpiece is naked, the action unfolding to stark, nerve-rattling silence. Only during the final scene, in which a dying Dix returns to his Kentucky farm, does the score offer any commentary on the film’s characters: the closing cue retains the main title’s aura of danger but introduces a harrowing, tragic melody, crying out for the life Dix (and on some level, all of the film’s criminals) longed for but could never achieve.

This premiere release of the soundtrack to The Asphalt Jungle features Rózsa’s main and end titles as well as the three source cues that survived—two of them by André Previn—remastered from ¼″ monaural tape of what were originally 35mm optical negatives.

- 14. Main Title 1M1

- An edgy cue underscores the film’s opening credits and continues through a sequence in which a police car pursues “hooligan” thief Dix (Sterling Hayden) through the barren streets of a nameless city. Emphasizing low colors throughout, the music evokes a dangerous atmosphere for the town with grunting, “jungle” rhythms and an Eastern-flavored chromatic melody.

- 15. Hamburger Joint #1 1M2

- With the police closing in on him, Dix steps into a restaurant owned by his hunchbacked criminal friend, Gus (James Whitmore). A relaxing piece for small jazz combo (composed by Alexander Hyde) plays on the radio as Gus hides Dix’s gun before the police arrive to take the hooligan downtown. (Hyde wrote and recorded a second piece of source music for the hamburger joint, but it was not used in the film and does not survive on the master tapes.)

- 16. Don’t Leave Your Guns (Jitterbug #1) 12M1

- At the conclusion of the film, the police crack down on the jewel thieves, prompting criminal mastermind Doc (Sam Jaffe) to flee town in a cab. He and his driver stop at a café, where Doc watches lecherously as a young girl dances to a rambunctious jazz band number (composed by André Previn) playing on a jukebox.

- 17. What About the Dame (Jitterbug #2) 12M2

- Instead of leaving when he has the chance, Doc lingers in the cafe and gives the girl some money so that she can dance to a second piece of energetic jukebox jazz, also composed by Previn. While Doc ogles the girl, the police surreptitiously arrive at the café and arrest him. (A third piece of source music, “First Jitterbug” by Earl Brent, appears in the film, but does not survive on the film’s master tapes.)

- 18. Dix’s Demise 13M1

- The film’s final sequence has Dix and his loyal prostitute girlfriend, Doll (Jean Hagen), speeding down a rural Kentucky road: Dix has been shot and is determined to revisit his family’s old horse farm before he dies. Biting, rhythmic material recalls Rózsa’s main title music as Dix races against death, but the cue’s threatening tone surrenders to a fateful, perfect fourth-laden melody—its latter half developed out of the score’s opening exotic theme—when the couple arrives at the farm. Dix makes his way onto the property before collapsing to the ground, a group of horses inspecting his body as Doll weeps and runs inside to fetch help. The end titles play out to a final gasp of the new theme for the tragedy of Dix and his morally corrupt brethren. —